Southport began the 1925–26 season with a sense of optimism. The previous campaign had carried the hope of promotion, and with the majority of the players returning there was every reason to believe progress could continue. Instead, the year became one of the most difficult in the club’s Football League history. By the spring, Southport were hanging on to their place in the Third Division North and only just avoided the need for re-election.

Having not dropped out of the top 4 for the entirety of the previous campaign, the Directors of the club had appointed Tom E. Maley as team manager in May, preparing for an expected assault on the Second Division. Maley, an experienced campaigner, was an FA Cup winner with Manchester City and had taken Bradford Park Avenue to the First Division during a spell which lasted eleven years.

He lasted only until the end of October.

The collapse was hard to foresee. Injuries played their part, but it was perhaps the loss of trainer Frank Jefferis, who returned to Preston, that was most keenly felt. Jefferis had provided authority and organisation. Without him, the team never looked the same.

There were glimpses of encouragement. Elias MacDonald, a direct winger, was ever-present, while George Sapsford, a £250 signing from Manchester United, briefly impressed. Local forward Johnny Ball scored a hat-trick against Wigan Borough before moving on to Sheffield Wednesday. Yet these were isolated moments in a season defined by disappointment.

For years Southport had relied on defensive strength. In 1924-25 only one side had conceded fewer in the division. It was a club record at just 37.

In 1925–26 that record has disintegrated by Christmas. Billy Little, the most reliable of half-backs, struggled, and even goalkeeper Billy ‘Salty’ Halsall, first choice since 1921, was eventually dropped.

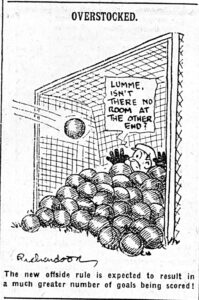

Part of the story lay in the wider game. That summer the International Football Association Board rewrote the offside law, reducing the requirement from three defenders to two. The change was intended to encourage more attacking football after years of low-scoring matches that had begun to frustrate supporters. Trial games had shown it would lead to more goals, but few grasped the scale of the difference it would make once the season began. In the First Division alone, more than 500 additional goals were scored compared to the year before.

Some clubs adapted quickly with new defensive systems. Others did not. Southport were caught out, and it took until the fifth game of the season to register a win, conceding 11 in the first four.

As the season progressed, combined with the loss of a number of players through injury the losses mounted and a 0-9 reverse against Manchester United in the Lancashire Senior Cup just added to the misery of an already poor start to the season. If there had been any hope of a change in fortunes from the festive period, that was put to bed with a 1-6 loss at Doncaster on Boxing Day.

Within a single week in April Southport were beaten 0-5 at Hartlepools, 1-6 at Bradford Park Avenue and 1-7 at home to Rochdale. That last defeat remains the heaviest in the club’s Football League history at Haig Avenue.

Tom Maley’s brother, Willie, the secretary and manager of the Celtic Football Club in Glasgow was an outspoken critic of the change of rules, suspicious of any change that might threaten his sides scientific play. It would not be unreasonable to assume his brother might have shared his views. That said, Willie’s Celtic romped to the title regardless.

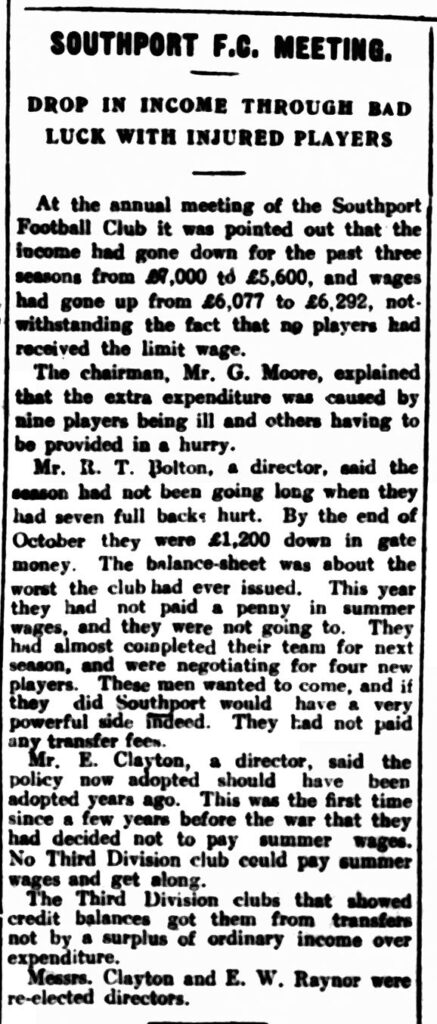

Support dwindled as results declined. Gate receipts fell from almost £7,000 to just £5,683 and the club posted a loss of more than £2,000. Secretary Edwin Clayton, in post since 1908, resigned but was appointed a director. Trainer Jimmy Fraser and groundsman Thompson also departed as part of a drive to reduce costs.

There was at least some relief in the FA Cup. Southport reached the third round before losing at Southend United in a match overshadowed by refereeing decisions that even drew the attention of the Football Association. It was stated in the Athletic News that “the referee blew his whistle for a goal-kick for Southport, believing that the ball had passed out of play, that Southport eased up, and a Southend player reached the ball and so enabled the home team to score, the referee consulting a linesman and granting a goal.” It was however the first goal in a match that Southport lost 5-2 – there was little point in making a formal protest.

Southport were not alone in struggling to adjust, but the scale of their defeats and the depth of their financial losses made the impact especially harsh. For the club, the lesson was clear. Membership of the Football League could not be taken for granted. Heavy defeats, falling crowds and financial strain left Southport close to the edge.

The squad was cut back heavily at the end of the season. Little moved to Lancaster Town, Jack Barber went to Halifax, Fergus Aitkin joined Bradford Park Avenue and even MacDonald, ever-present throughout the year, was released and signed for Barrow.

One addition proved far more lasting. Edgar Raynor, a local fishmonger and Methodist layman, joined the board and would remain a director for 32 years, 26 of them as chairman.

The year was turbulent across the region. Manchester City suffered the extraordinary double of reaching the FA Cup Final while also being relegated from the First Division. Stoke, newly renamed Stoke City, dropped into the Third Division North. At the other end of the scale, Huddersfield Town secured a third successive league title, the first club to do so.

One hundred years on, the story of 1925–26 is a reminder of how quickly circumstances can change, and how much a club depends on adapting to the wider forces shaping the game.

Disclaimer: This article draws on the research of Michael Braham and Geoff Wilde, in particular their book The Sandgrounders: The Complete League History of Southport FC. Additional sources are the British Newspaper Archive, and any errors of interpretation are my own.

Discover more from Southport Central

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

1 - 1 v Chorley (H) 21/10/2025

1 - 1 v Chorley (H) 21/10/2025

More Stories

The Price Of Saying No

Friday Night Football

Fifty Years On: Counting the Cash, Missing the Moment