Few topics divide supporters more than walk-out music. For Southport, the debate circles endlessly back to Da Do Ron Ron, a song still regarded by many as “our tune”. Its place in the matchday ritual is far from settled, and every so often the question resurfaces: is it tradition worth preserving, or atmosphere holding us back?

The most recent round of discussion was sparked by Nicola’s return to the tannoy, which happened to coincide with a change of music. Some pointed the finger at her, but that misses the point. The choice of walk-out song has never rested with one individual, and Nicola’s role on Saturday was simply to cue what had been chosen. What it did do, though, was re-ignite the wider debate.

Like most clubs, the soundtrack at Haig Avenue has been shaped by trial and error, circumstance and tradition, and the truth is that Da Do Ron Ron has never been as permanent as some might assume.

A History of Changing Tunes

There have been long stretches where Da Do Ron Ron has not been played at all. In the 1992/93 season, the players ran out to All Together Now by The Farm. The first two Conference seasons opened to I’m the Leader of the Gang (I Am) by Gary Glitter, quickly dropped for obvious reasons. Other experiments followed; Ready to Go by Republica, Hey Boy Hey Girl by The Chemical Brothers, Right Here, Right Now by Fatboy Slim, and countless others.

Walk-out music, like in boxing, darts or rugby league, is about atmosphere. It should be uplifting, energising and instantly recognisable. Yet for many supporters, if you asked what Southport’s song is, they would, almost inexplicably, answer Da Do Ron Ron.

Whose Song Is It Anyway?

This is the strange part. The songs actually sung with passion on the terraces – Twist and Shout in particular – probably have more genuine claim. The Beatles’ classic has a local connection, it came from the stands rather than the PA system, and it has the energy to rouse a crowd. Da Do Ron Ron, by contrast, was imported.

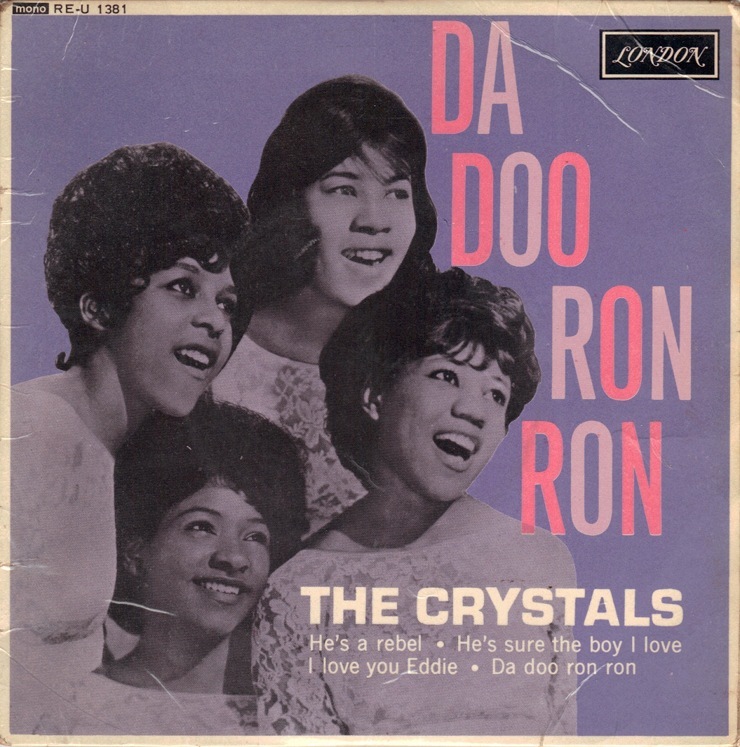

The song has no connection to Southport, the town or the club. It is a song written by American songwriters Jeff Barry, Ellie Greenwich and Phil Spector and it first became a popular hit single for the American girl group the Crystals. It entered the Top 40 in the second week of May, 1963 and eventually rose to number 3 in the US Billboard Charts. By comparison it peaked at number 5 in the UK. By most accounts, it became associated with Haig Avenue in the late 70s simply because Ron Ellis used it as his radio signature tune, and carried it over to the ground. Its endurance owed more to playful egotism than to terrace adoption or club success. The catchy line of “Da Do Ron Ron” doesn’t even mean anything. Spector admitted to it being gobbledegook made up on the spot in his New York office to separate the verses until proper lyrics could be written, before deciding that he liked it.

Club historian Mike Braham is clear:

“Da Do Ron Ron was nothing more than Ron Ellis’ signature tune and has nothing to do with SFC whatsoever.”

He recalls that when he first went to Haig Avenue there were six or seven regular records before kick-off: If You’re Irish, The Teddy Bears’ Picnic, Around the World in 80 Days, snippets from Capstan and Bristol cigarette adverts, and the march Blaze Away, which was always used to finish the sequence. Braham persuaded the club to play Blaze Away again immediately after Geoff Wilde’s death, because it was a tradition both men appreciated.

He also remembers Southport Journal journalist Len Peet writing a scathing piece in his Shots from All Angles column in the mid-60s about “the din of pop music” at half-time, when many fans preferred peace and quiet to discuss the first half.

That picture puts Da Do Ron Ron in perspective. Far from being the anthem of Southport’s “golden era”, it only came to prominence in the club’s final league years and the bleak early non-league seasons, hardly a period looked back on with any longing and fondness.

Why Some Songs Stick

So why have other clubs managed to find music that works? The answer usually lies in three ingredients: local connection, terrace adoption, and association with success.

Everton: Z-Cars was a BBC police drama filmed locally, with Liverpudlian actors. The Toffees adopted it in 1962/63, coinciding with a league title. The siren that precedes it still raises goosebumps today, and crucially it is used as the walk-out.

Newcastle United: Local Hero was written by Geordie musician Mark Knopfler. Adopted in the early 1990s, it became entwined with the Keegan era. Again, this is the walk-out music — and it works because of its local tie and timing with success.

Most other famous football songs are not walk-outs at all, but anthems woven into matchday tradition:

Liverpool: You’ll Never Walk Alone began as a terrace chant and is sung before kick-off, but not used for the entrance.

Manchester City: Blue Moon is belted out by the fans during games.

West Ham: I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles is sung from the terraces, and played when the players are already out on the pitch prior to kick off.

Ajax: Three Little Birds became a post-match ritual after a friendly in Cardiff, later embraced by the club.

Nottingham Forest: Mull of Kintyre was first sung on the terraces during their late-70s glory years and only much later adopted more formally by the club.

The point is clear. Songs like these belong to the supporters. They work because the crowd sings them, not because the PA dictates them. They create identity and atmosphere, but they are not walk-out tunes.

Where Does Da Do Ron Ron Sit?

By that measure, Da Do Ron Ron probably falls into the “club association” category. It is undeniably “Southport’s song” in the sense that it has been played often enough to become linked with us. But, like Mull of Kintyre at Forest or Three Little Birds at Ajax, that does not automatically make it the right track for the players to emerge to.

The walk-out should be something different: something that lifts the ground in the moment, as Z-Cars does at Goodison/Bramley Moore or Local Hero does at St James’ Park.

The Owners’ Role

To their credit, the new majority shareholders are mindful of this balance between heritage and atmosphere. David Cunningham in particular reached out to me, as a club historian, to ask about the significance of Da Do Ron Ron. That shows a genuine awareness of tradition.

In the absence of a recognised formal fan body there is only so much they can do – they cannot consult with everybody. Even amongst supporters on Port Chat there isn’t universal agreement on where it should sit in the matchday ritual, if at all. At July’s fans’ forum Kieran Malone admitted that not everything they try will work. Indeed, it would be unreasonable to expect otherwise. What matters is the willingness to try to make positive changes, and that should be applauded and supported.

In truth, I don’t think that this is the hill to die on. Pick your battles. Make sure it is a worthwhile cause you’re fighting for. If they want to move us to Scarisbrick and make us play in blue – that’s different, and that’s territory where the Independent Football Regulator would insist on proper consultation as it is considered a genuine heritage matter.

Atmosphere Matters

The walk-out moment is not the time for sentimentality. It is the time to lift the ground, raise anticipation and energise players. Done right, it can be electric. At Goodison Park, the Z-Cars siren does it. At St James’ Park, the opening bars of Local Hero do it. At Virginia Tech in the US, Enter Sandman by Metallica turns the stadium into a shaking mass as 60,000 fans jump in unison.

The important thing is that walk-out music doesn’t need to be unique to the club. What matters is whether it achieves its purpose; raising the atmosphere, connecting with the crowd, and giving players a sense of lift.

At Haig Avenue, Da Do Ron Ron has never had that effect. Younger fans often do not even know what it is, or what it has to do with a non-league club in the north-west of England.

None of this means throwing it away altogether. Tradition has a place. Perhaps Da Do Ron Ron could be played after the teams are out, or reserved for certain moments such as in celebration of a win, as a nostalgic nod. But as the players walk out, the club should be aiming for atmosphere.

The real question is not “what is Southport’s song?” If you asked, most would still answer Da Do Ron Ron regardless of it’s origin. The real question is “what works as walk-out music?”

Sometimes tradition deserves to be preserved. Sometimes it deserves to be questioned and moved aside. The walk-out is one of those moments where atmosphere matters more.

Disclaimer: This article is written in an independent capacity for Southport Central. It reflects personal research, recollections and interpretation of the club’s history and traditions. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, the views expressed are those of the author and not of Southport Football Club or its majority shareholders.

Sources: “Tearing Down The Wall of Sound: The Rise And Fall of Phil Spector”, By Mick Brown

Discover more from Southport Central

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

1 - 1 v Chorley (H) 21/10/2025

1 - 1 v Chorley (H) 21/10/2025

More Stories

The Price Of Saying No

Friday Night Football

Fifty Years On: Counting the Cash, Missing the Moment